The Disruptive Administrator: Tread with Care

Friday, August 5, 2016 at 8:00AM

Friday, August 5, 2016 at 8:00AM Richard A. Robbins, MD

Phoenix Pulmonary and Critical Care Research and Education Foundation

Gilbert, AZ

Abstract

Although the extent of disruptive behavior in healthcare is unclear, the courts are beginning to recognize that administrators can wrongfully restrain a physician's ability to practice. Disruptive conduct is often difficult to prove. However, when administration takes action against an individual physician, they are largely powerless, with governing boards and courts usually siding with the administrators. As long as physicians remain vulnerable to retaliation and administration remains exempt for inappropriate actions, physicians should carefully consider the consequences before displaying any opposition to an administrative action.

Introduction

Over the past three decades there have been hundreds of articles published on "disruptive" physicians. Publications have appeared in prestigious medical journals and been published by medical organizations such as the American Medical Association and by regulatory organizations such as the Joint Commission and some state licensing agencies. Although attempts have been made to define disruptive behavior, the definition remains subjective and can be applied to any behavior viewed objectionable by an administrator. The medical literature on disruptive physician behavior is descriptive, nonexperimental and not evidence based (1). Furthermore, despite claims to the contrary, there is little evidence that "disruptive" behavior harms patient care (1).

Certainly, there are physicians who are disruptive. Most disruptions are due to conflict between physicians and other healthcare providers with which they most closely interact, usually nurses. Not surprisingly, many of the authors of these descriptive articles have been nurses although some have been administrators, lawyers or even other physicians. These articles often give the impression that administrators are merely trying to do their job and that physicians who disagree should be punished. Although this may be true, and most administrators are trying their best to have a positive impact on health care delivery, in some instances it is not.

Like disruptive physician behavior, the extent and incidence of disruptive administrative behavior is unknown. A PubMed search and even a Google search on disruptive administrative behavior discovered no appropriate articles. However, one type of disruptive behavior is bullying. A recent survey in the United Kingdom of obstetrics and gynecology consultants suggests the problem may be common. Nearly half of the consultants who responded to a survey said they had been persistently bullied or undermined on the job (2). Victims report that those at the top of the hierarchy or near it, such as lead clinicians, medical directors, and board-level executives, do most of the bullying and undermining. Pamela Wible MD, an authority in physician suicide prevention, said these results are not unique to the United Kingdom, and that the patterns are similar in the United States (3).

A major difference between physician and administrative disruptive behavior is that physician disruptive behavior usually applies to a specific individual but most of the examples detailed below are largely system retaliation against physicians who complained. Administrators typically work through committees thereby diffusing their individual responsibility for a specific action. Wible said the usual long list of perpetrators against physicians often indicates a toxic work environment (3). "I talk to doctors every day who are ready to quit medicine because of this toxic work environment that has to do with this bullying behavior. What I hear most is it's coming from the clinic manager or the administrative team who calls the doctor into the office and beats them up ..." she added.

History of the Recognition of Physician Disruptive Behavior

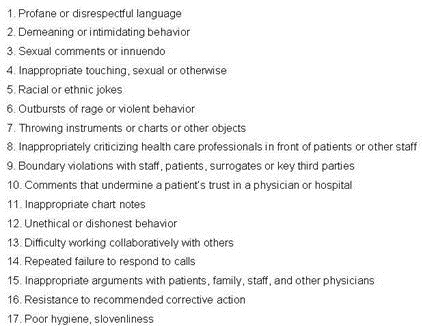

Isolated articles on disruptive physician behavior first appeared in the medical literature in the 1970's with scattered reports appearing through the 1980's and 1990's (4). Prompted by these isolated reports and the perception that this might be a growing problem, a Special Committee on Professional Conduct and Ethics was appointed by the Federation of State Medical Boards to investigate physician disruptive behavior. They released their report in April, 2000 and listed 17 behavioral sentinel events (Table 1) (5).

Table 1. Behavioral sentinel events (3).

As announced in 2008 in an article in "The Joint Commission Journal of Quality and Patient Safety" and a Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alert, a new Joint Commission accreditation standard requires hospitals to have a disruptive policy in place and to provide resources for its support as one of the leadership standards for accreditation (6,7). Although not stated, it is clear these standards refer to hospital employees and not hospital administration giving the impression that any disagreement between a physician or other employee and administration are the result of a disruptive behavior on the part of the physician or employee. They imply that all adverse actions against physicians for disruptive physician behavior are warranted. However, physicians may be trying to protect their patients from poor administrative decisions while administrators view physician opposition as insubordination. The viewpoint lies in the eyes of observer.

Disruptive Administrative Behavior Involving Whistleblowing

Klein v University Of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

Sanford Klein was chief of anesthesiology at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Brunswick, NJ, for 16 years (8). He grew increasingly concerned about patient safety in the radiology department and complained repeatedly to the hospital's chief of staff, citing insufficient staff, space, and resuscitation equipment. After Klein grew increasingly vocal he was required to work under supervision. He refused to accept that restriction and sued. The trial judge granted summary judgment for the defendants, and an appellate court upheld that ruling. Klein is still a tenured professor at the university, but he no longer has privileges at the hospital. "This battle has cost me hundreds of thousands of dollars so far, and it's destroyed my career as a practicing physician," he says. "But if I had to do it over again, I would, because this is an ethical issue."

Lemonick v Allegheny Hospital System

David Lemonick was an emergency room physician at Pittsburgh's Western Pennsylvania Hospital who repeatedly complained to his department chairman about various patient safety problems (8). His department chairman accused him of "disruptive behavior". Lemonick wrote to the hospital's CEO to express his concerns about patient care, who thanked him, promised an investigation, and assured him there would be no retaliation. Nevertheless, Lemonick was terminated and sued the hospital for violating Pennsylvania's whistleblower protection law and another state law that specifically protects healthcare workers from retaliation for reporting a "serious event or incident" involving patient safety. Lemonick and Alleghany reached an out of court settlement and he is now director of emergency medicine at a small hospital about 50 miles from his Pittsburgh. He was named Pennsylvania's emergency room physician of the year in 2007.

Ulrich v Laguna Honda Hospital

John Ulrich protested at a staff meeting when he learned that Laguna Honda Hospital was planning to lay off medical personnel, including physicians (9). He claimed layoffs would endanger patient care. Ulrich resigned and the hospital administration reported his resignation to the state board and the National Practitioner Data Bank, noting that it had followed unknown to Ulrich "commencement of a formal investigation into his practice and professional conduct". Although the state board found no grounds for action, the hospital refused to void the NPDB report. Ulrich sued the hospital and its administrators. In 2004, after a long legal battle, Ulrich won a $4.3 million verdict, and later settled for about $1.5 million, with the hospital agreeing to retract its report to the NPDB. Still, he spent nearly seven years without a full-time job, doing part-time work as a coder and medical researcher, with a sharply reduced income.

Schulze v Humana

Dr. John Paul Schulze, a longtime family practice doctor in Corpus Christi, Texas, criticized Humana Health Care in 1996 for its decision to have its own doctors care for all patients once they were admitted to Humana hospitals (9). Humana officials alleged that he “was unfit to practice medicine, and represented an ongoing threat of harm to his patients" and reported Schulze to the National Practitioners Data Bank and the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners. Schulze sued and after several years of legal battles an out of court settlement was reached.

Flynn v. Anadarko Municipal Hospital

Dr. John Flynn reported to Anadarko Municipal Hospital administrators that a colleague abandoned a patient (9). After no action was taken, he resigned from the medical staff before reporting the alleged violations to state and federal authorities. Flynn attempted to rejoin the staff after an investigation had found violations, but the medical staff denied him privileges. The public works authority governing the hospital held a lengthy hearing on the case and restored Flynn's privileges.

Kirby v University Hospitals of Cleveland

University Hospitals of Cleveland (UH) which is affiliated with Case Western Reserve University recruited Dr. Thomas Kirby to head up its cardiothoracic surgery and lung transplant divisions in 1998 (9). Not long after he joined UH, Kirby started pressing hospital executives about program changes, particularly for open heart procedures. Kirby said he was alarmed by mounting deaths and complications among intensive care patients after heart surgeries, and took his concerns to hospital administrators and board members.

When he returned from a vacation, Kirby learned he'd been demoted and the two colleagues he'd recruited to the program had been fired. During the subsequent months, acrimony within the department boiled over and eventually led to Kirby filing a slander suit against a fellow surgeon, who Kirby claimed made disparaging remarks to other staff members about his clinical competence. The hospital's reaction was to suspend Kirby. The suspension letter from the hospital chief of staff accused Kirby of being "abusive, arrogant and aggressive" with other hospital staff, including use of profanity and "foul and/or sexual language." Accusers were not named, dates were not supplied and Kirby was not offered the chance to continue practicing surgery. Subsequently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education revoked UH's cardiothoracic surgery residency, saying the program no longer met council standards.

However, Kirby sued over another issue which may have been at the heart of the acrimony. Kirby had alleged that UH had entered into improper financial arrangements with doctors to induce them to refer patients and then billed Medicare for the services provided. The U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Ohio intervened in the suit. University Hospital eventually agreed to pay $13.9 million to settle the federal false claims lawsuit arising from alleged anti-kickback violations although they denied any wrongdoing. Kirby was awarded a settlement of $1.5 million.

Fahlen vs. Memorial Medical Center

Between 2004 and 2008, Dr. Mark Fahlen, reported to hospital administration that nurses at Memorial Medical Center in Modesto, California were failing to follow his directions, thus endangering patients’ lives (10). However, the nurses complained about Fahlen’s behavior and he was fired. A peer committee consisting of six physicians reviewed the decision and found no professional incompetence but Memorial’s board refused to grant him staff privileges. Subsequently, Fahlen sued. After four years of legal wrangling, an out of court agreement reinstated Fahlen's hospital privileges.

Disruptive Administrative Behavior By an Individual Administrator

Vosough vs. Kierce

In Patterson, New Jersey Khashayar Vosough MD and his partners sued St. Joseph's Regional Medical Center's obstetrics and gynecology department chairman, Roger Kierce MD, for profane language and abusive and demeaning behavior (11). Kierce once told a group of doctors he would "separate their skulls from their bodies" if they disobeyed him. In 2012 a Bergen County jury returned the verdict in less than an hour, awarding Vosough and his colleagues $1,270,000. However, the decision was appealed and overturned in 2014 by the Superior Court of New Jersey, Appellate Division (12).

Medical Staff Collectively Suing a Hospital Administration

Medical Staff of Avera Marshall Regional Medical Center v. Avera Marshall

In rare instances a collection of physicians comes into legal conflict with a hospital. In Minnesota the medical staff of Avera Marshall Medical Center was charged with physician credentialing, peer review, and quality assurance (13). A two-thirds majority vote was required to change the bylaws but the hospital administration unilaterally changed the bylaws in early 2012. The medical staff sued the hospital.

However, the real source of the dispute might be over patient referrals and income. Conflict arose when doctors not employed by the hospital alleged that the that the hospital was steering emergency room patients toward its own employed doctors. The case was eventually decided by the Minnesota Supreme Court who ruled in favor of the medical staff (13).

Discussion

These cases illustrate that physicians can occasionally win lawsuits against hospital administration for disruptive behavior. However, victory is often hollow with careers destroyed and years without a professional income as the wheels of justice slowly turn. As one article said, "Is whistleblowing worth it?" (8).

Dr. Fahlen was fortunate that the peer review found no professional incompetence. In many instances the reviews are conducted by physician administrators with the verdict predetermined. For example, in the Thomas Kummet case presented in the Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care, an independent review concluded there was no malpractice (14). However, the Veterans Administration had the case reviewed by a VA appointed committee who sided with the VA administration. Kummet's name was subsequently submitted to the National Practioner Databank and he sued the VA. After the case was dismissed by a Federal court, Kummet left the VA system.

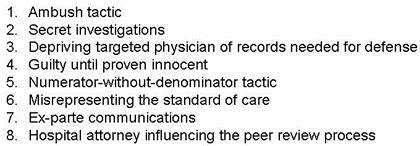

Physicians are particularly vulnerable to retaliation by unfounded accusations. Several examples were given above. In many of these cases, complaints were followed by what appeared to be a sham peer review. Sham peer review is a name given to the abuse of the peer review process to attack a doctor for personal or other non-medical reasons (15,16). The American Medical Association conducted an investigation of medical peer review in 2007 and concluded that it is easy to allege misconduct and 15% of surveyed physicians by the Massachusetts Medical Society indicated that they were aware of peer review misuse or abuse (17). However, cases of malicious peer review proven through the legal system are rare.

Huntoon (18) listed a number of characteristic of sham peer review (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of sham peer review (16).

I first witnessed peer review being used as a weapon as a junior faculty member in the mid-1980's. The then chief of thoracic surgery, a pediatric thoracic surgeon, underwent peer review. It appeared that the underlying reason was that most of his operations were performed at an affiliated children's hospital rather than the university medical center that conducted the review. The influence of income as opposed to medical quality being the real motivation for an administrative action against a physician is unknown, although some of the above cases suggests it is not uncommon. Given the amount of money potentially involved and the lack of consequences for hospital administration, it is naive to believe that false accusations would not or will not continue to occur.

Most disturbing is physicians who falsely accuse other physicians. Although this behavior would clearly be covered by behavioral sentinel events such as those listed in table 1, hospital boards may deem not to act. For example, one physician accused a hospital director, a non-practicing physician, of being disruptive. The hospital board failed to act stating that their interpretation was that the term disruptive physician applied only to practicing physicians.

The federal Whistle Blower Protection Act (WPA) protects most federal employees who work in the executive branch. It also requires that federal agencies take appropriate action. Most individual states have also enacted their own whistleblower laws, which protect state, public and/or private employees. Unlike their federal counterparts however, these state levels generally do not provide payment or compensation to whistleblowers, Instead the states concentrate on the prevention of retaliatory action toward the whistleblower. Unlike California's law specifically protecting physicians most state laws are not specific to physicians.

Although beyond the scope of this review, it seems likely that administrative disruptive actions may also occur against other health care workers including nurses, technicians and other staff. However, the prevalence and appropriateness of these actions are unclear. However, as leaders of the healthcare team and often not employed by the hospital, physicians are unique as evidenced by the National Practioner Data Bank. No similar nursing, technician or administrator data bank exists.

Although the few cases cited above suggest that legal action can be successful against abusive administrators, these cases are rare. The consequences of being labeled disruptive can be dire to physicians who lack any due process either in hospitals and often in the courts. Until such a time when administration can be held accountable for behavior that is considered disruptive, the sensible physician might avoid conflicts with hospital administration.

References

- Hutchinson M, Jackson D. Hostile clinician behaviours in the nursing work environment and implications for patient care: a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2013 Oct 4;12(1):25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabazz T, Parry-Smith W, Oates S, Henderson S, Mountfield J. Consultants as victims of bullying and undermining: a survey of Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists consultant experiences. BMJ Open. 2016 Jun 20;6(6):e011462. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frellick M. Senior physicians report bullying from above and below. Medscape. June 29, 2016. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/865561?src=WNL_jumpst_160704_MSCPEDIT&impID=1143310&faf=1%23vp_2#vp_2

- Hollowell EE. The disruptive physician: handle with care. Trustee. 1978 Jun;31(6):11-3, 15, 17. [PubMed]

- Russ C, Berger AM, Joas T, Margolis PM, O'Connell LW, Pittard JC, George A. Porter GA, Selinger RCL, Tornelli-Mitchell J, Winchell CE, Wolff TL. Report of the Special Committee on Professional Conduct and Ethics. Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States. April, 2000. Available at: https://www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/2000_grpol_Professional_Conducts_and_Ethics.pdf (accessed 5/3/16).

- Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:464–471. [PubMed]

- The Joint Commission. Behaviors That Undermine a Culture of Safety Sentinel Event Alert #40 July 9, 2008: 1-5. Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_40_behaviors_that_undermine_a_culture_of_safety/ (accessed 5/3/16).

- Rice B. Is whistleblowing worth it? Medical Economics. January 20, 2006. Available at: http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/content/whistleblowing-worth-it (accessed 5/5/16).

- Twedt S. The Cost of Courage: how the tables turn on doctors. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. October 26, 2003. Available at: http://www.post-gazette.com/news/nation/2003/10/26/The-Cost-of-Courage-How-the-tables-turn-on-doctors/stories/200310260052 (accessed 5/5/16).

- Danaher M. Physician not required to exhaust hospital’s administrative review process before suing hospital under state’s whistleblower statute. Employment Law Matters. February 20, 2014. Available at: http://www.employmentlawmatters.net/2014/02/articles/health-law/physician-not-required-to-exhaust-hospitals-administrative-review-process-before-suing-hospital-under-states-whistleblower-statute/ (accessed 5/3/16).

- Washburn L. Doctors win suit against hospital over abuse by boss. The Record. January 11, 2012. Available at: http://www.northjersey.com/news/doctors-win-suit-against-hospital-over-abuse-by-boss-1.847838?page=all (accessed 5/4/16).

- Ashrafi JAD. Vosough v. Kierce. Find Law for Legal Professionals. 2014. Available at: http://caselaw.findlaw.com/nj-superior-court-appellate-division/1676593.html (accessed 5/4/16).

- Moore, JD Jr. When docs sue their own hospital-at issue: who has authority to hire, fire, and discipline staff physicians. Medpage Today. January 19, 2015. Available at: http://www.medpagetoday.com/PracticeManagement/Medicolegal/49610 (accessed 5/3/16).

- Robbins RA. Profiles in medical courage: Thomas Kummet and the courage to fight bureaucracy. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2013;6(1):29-35. Available at: http://www.swjpcc.com/general-medicine/2013/1/12/profiles-in-medical-courage-thomas-kummet-and-the-courage-to.html (accessed 8/5/16)

- Chalifoux R Jr, So what is a sham peer review? MedGenMed. 2005 Nov 15;7(4):47. [PubMed]

- Langston EL. Inappropriate peer review. Report of the board of trustees. 2016. Available at: http://shammeddoc.blogspot.com/2010/10/american-medical-association-ama-and.html (accessed 5/15/16).

- Chu J. Doctors who hurt doctors. Time. August 07, 2005. Available at: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1090918,00.html (accessed 5/15/16, requires subscription).

- Huntoon LR. Tactics characteristic of sham peer review. Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons 2009;14(3):64-6.

Cite as: Robbins RA. The disruptive administrator: tread with care. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016:13(2):71-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc049-16 PDF

Reader Comments